Khalid Abo Middain used his hands, a hammer and a small shovel to build his own shelter on the outskirts of a fast-growing refugee camp near Rafah City in southern Gaza.

The father-of-three arrived there with his family after fleeing four times from Israel’s war against Hamas over the course of three months.

They originally left Bureij refugee camp in central Gaza after the war broke out and are unsure of what remains of their family home.

“I do not know how it is, because there is no means of communication at the moment,” he said, looking out at rows of makeshift tents.

“What is important is to find yourself in a place where you stay temporarily till this dark cloud is cleared.”

One hundred days into the war between Israel and Hamas, much of Gaza lies in ruins. Architecture and human rights experts say the scale of destruction and displacement is “immense” and unlike anything they’ve seen in Gaza before.

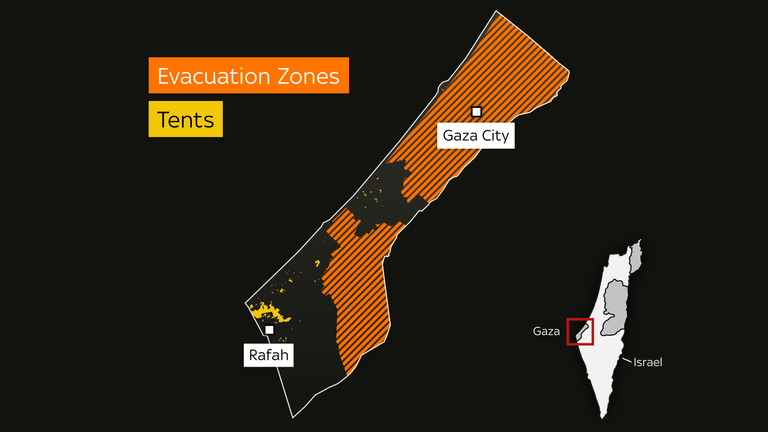

Since the start of the war, 1.9 million people have been displaced from their homes, according to the UN, and Rafah governorate is now the main refuge for those displaced. Over one million people have been crammed into a growing refugee camp that lies just north of Rafah City.

Satellite images show the camp’s expansion with an increasing number of makeshift shelters appearing on the outskirts of Rafah in just three weeks, between 3 and 31 December. The camp is the largest of its kind to emerge since the war began.

‘Everywhere is just so overcrowded’

“These spaces are not fit to hold the number of people that are being forced to live there,” said Nadia Hardman, a researcher at Human Rights Watch, who has been speaking to displaced Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, including Rafah. “Everywhere is just so overcrowded,” she told Sky News.

“What you have right now is more than half the population stuffed inside an area that was never meant to contain that many people. And the shelters that are being used are not designed for that purpose. So people are just making do, setting up tented spaces wherever they can.”

Satellite imagery from 6 January shows tents spilling out into the streets and parks of Rafah.

“We’ve never seen anything on this scale,” said Fatina Abreek-Zubiedat, assistant professor of architecture at Tel Aviv University, whose research focuses on transitional spaces in conflict zones.

By 6 January, the camp had exploded into a tent city of 2.9 sq km – equivalent to almost 400 football pitches.

The camp encompasses a UN facility, which was set up as a logistics hub for operations and as the main warehouse for basic food storage. It’s now doubling as a shelter, with hundreds of tents crowding inside and around the property.

“[People] are in an environment with limited to no services, with no reliable electricity, running water. So you can’t run a humanitarian operation in the way that you would want to,” said Hardman, the researcher at Human Rights Watch.

Rafah’s population has grown fourfold since the outbreak of war, according to the UN. The city lies along the border with Egypt, currently Gaza’s only access to the outside world. It is here where meagre aid supplies arrive, and where many Gazans await permission to flee the territory.

Aid organisations are under increasing pressure to provide humanitarian assistance to the growing number of people flooding the area.

“We’re gradually being cornered in a very restrictive perimeter in southern Gaza, in Rafah, with dwindling options to offer critical medical assistance, while the needs are desperately growing,” said Thomas Lauvin, Medecins Sans Frontieres project coordinator in Gaza.

Sky News journalists in Gaza visited the camp in Rafah.

Many of the residents have built their own tents. Children’s clothes hang from makeshift washing lines as Gazans queue to fill up bottles and buckets against the backdrop of a sea of tents. Some families have even built their own bathrooms.

Eman Ismail Zweidi and her family set up their shelter in the western part of the camp. The seven of them had fled Beit Hanoun the day the war started and have been on the move until recently settling in Rafah.

Violence seemed to follow them everywhere they went. Two days after they arrived in Rafah, they learned the buildings they had been staying at just days before in Khan Younis were hit.

“We became very distressed by moving from one place to another,” she said. “Every new place we moved into was more difficult than the previous one.”

On a crisp January afternoon, they gathered around Ms Zweidi’s phone, looking at images from their life before the war began. “Duaa! This is your first day in nursery. Do you remember when I photographed you and combed your hair?”, she said.

One of Ms Zweidi’s youngest daughters, Duaa, smiles at the camera, wearing pigtails and her school uniform.

“We could expect that these camps will exist not for months, but unfortunately, perhaps for years after the war will end,” said Irit Katz, associate professor of architecture and urban studies at Cambridge University, who has extensively researched the development of refugee camps in the Middle East and around the world.

The camp is on desert terrain and given the influx of displaced Gazans and limited supplies, conditions are worsening. The area lacks a sewage system and there is no running water or electricity. There is no centralised organisation inside the camp and families build their own homes.

“Usually, camps are created as temporary spaces that are supposed to exist only for a defined period. They’re not adequately linked to other environments,” said Ms Katz.

“People’s ability to inhabit them and to actually create a place that they could call home is very, very limited,” she said.

It’s difficult to gauge the exact number of people at the Rafah camp. And numbers keep growing as more people flee the violence farther north. It’s not just families, but also displaced individuals from areas in the north like Gaza City and Beit Hanoun.

Nearly two-thirds of the Gaza Strip is under Israeli evacuation orders, according to the UN.

In the remaining areas, satellite imagery analysed by Sky News shows that refugee camps made up largely of makeshift shelters have rapidly expanded.

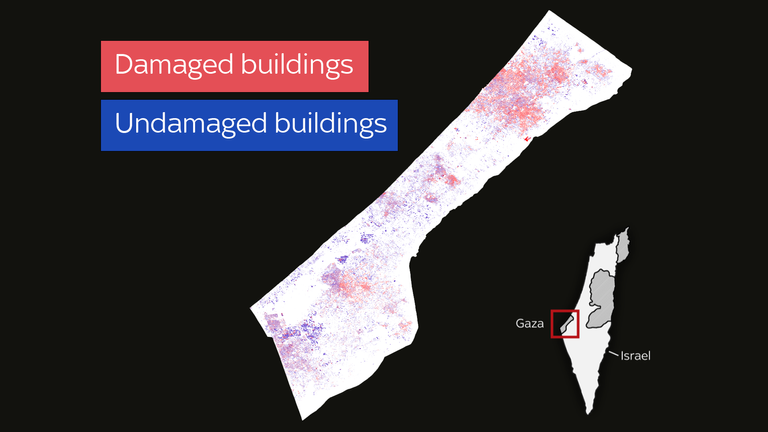

But for these Gazans who have fled to camps for safety, there is little or nothing to return to. Satellite radar data shows the extent of the damage to buildings from Israeli strikes.

The destruction is especially severe in the north, where Gaza City has seen some of the fiercest bombardment of the war.

“We are talking about years, if not decades, that it will take to rebuild the original homes and areas of those currently displaced,” said Ms Katz, the Cambridge professor.

Palestine Square, in Gaza City’s Rimal neighbourhood, was home to a mosque, a school for deaf children and a fruit market. Satellite images show that the square has been completely destroyed.

Just under three kilometres north of the square was Gaza’s Blue Beach Resort. It was once described as “the first luxurious seaside vacation spot in the Gaza Strip”, with more than 150 rooms, several swimming pools and dotted with palm trees.

In early January, the IDF claimed it had “demolished” a network of Hamas tunnels underneath the hotel.

In some heavily damaged areas, Israeli forces have left other marks of their presence.

The satellite images below show two Stars of David, a Jewish symbol used on the Israeli flag, marked outside a school in Beit Hanoun (left) on the campus of the Islamic University of Gaza, in Gaza City (right).

In central Gaza, the destruction is equally as stark.

Bureij is a Palestinian refugee camp located east of the Salah al-Din Road which runs from the north to the south of the strip. In five weeks, dozens of fields and houses less than two kilometres away from the border with Israel were destroyed.

Tobias Borck, a senior Research Fellow for Middle East Security at RUSI, a thinktank, told Sky News “the future for Gazans looks pretty grim,” and added that in the context of displaced people in this war differs from many others.

“Israel is essentially fighting a war in a completely closed-off piece of territory. The people that live in Gaza cannot go anywhere,” he said.

“There are a few things about this war that are absolutely unique, and one is this question around refugees and displaced people… in the Israeli-Palestinian context, history suggests to the Palestinian people that every time they become refugees, they leave an area, and they are not able to go back.”

As for the future of who governs Gaza, Mr Borck said there has been some “push back” from the Israeli government to the international community to outline a plan for what comes next after the war.

“How is that going to happen? Who is going to pay for it? It remains a completely unanswered question”, said Mr Borck of rebuilding and finding political control in Gaza.

“This next challenge is at a completely different scale,” he said.

“For quite a long time we will be watching what is a devastating, unsustainable humanitarian crisis that is sustained because no one comes up with a workable solution.”

Additional reporting from Sky News’ Gaza team.

The Data and Forensics team is a multi-skilled unit dedicated to providing transparent journalism from Sky News. We gather, analyse and visualise data to tell data-driven stories. We combine traditional reporting skills with advanced analysis of satellite images, social media and other open source information. Through multimedia storytelling we aim to better explain the world while also showing how our journalism is done.